Chapter 11 Functional Programming in JS

Despite it’s name, the JavaScript language was based more on Scheme than it was on Java. Scheme is a functional programming language, which means it follows a programming paradigm centered on functions rather than on variables, objects, and statements as you’ve done before (known as imperative programming). An alternative to object-oriented programming, functional programming provides a framework for thinking about how to give instructions to a computer. While JavaScript is not a fully functional language, it does support a number of functional programming features that are vital to developing effective and interactive systems. This chapter introduces these functional concepts.

11.1 Functions ARE Variables

Normally you’ve considered functions as “named sequences of instructions”, or groupings of lines of code that are given a name. But in a functional programming paradigm, functions are first-class citizens—that is, they are “things” (values) that can be organized and manipulated just like variables.

In JavaScript, functions ARE variables:

//create a function called `sayHello`

function sayHello(name) {

console.log("Hello, "+name);

}

//what kind of thing is `sayHello` ?

console.log(typeof sayHello); //=> 'function'Just like let x = 3 defines a variable for a value of type number, or let msg = "hello" defines a variable for a value of type string, the above sayHello function is actually a variable for a value of type function!

Important: we refer to a function by it’s name without the parentheses!

The fact that functions are variables is the core realization to make when programming in a functional style. You need to be able to think about functions as things (nouns), rather than as behaviors (verbs). If you imagine that functions are “recipes”, then you need to think about them as pages from the cookbook (that can be bound together or handed to a friend), rather than just the sequence of actions that they tell you to perform.

And because functions are just another type of variable, they can be used anywhere that a “regular” variable can be used. For example, functions are values, so they can be assigned to other variables!

//create a function called `sayHello`

function sayHello(name) {

console.log("Hello, "+name);

}

//assign the `sayHello` value to a new variable `greet`

let greet = sayHello;

//call the function assigned to the `greet` variable

greet("world"); //logs "Hello world"- It helps to think of functions as just a special kind of array. Just as arrays have a special syntax

[](bracket notation) that can be used to “get” a value from the list, functions have a special syntax()(parentheses) that can be used to “run” the function.

Anonymous Functions

Functions are values, just like arrays and objects. And just as arrays and objects can be written as literals which can be anonymously passed into functions, JavaScript supports anonymous functions:

var array = [1,2,3]; //named variable (not anonymous)

console.log(array); //pass in named var

console.log( [4,5,6] ); //pass in anonymous value//named function (normal)

function sayHello(person){

console.log("Hello, "+person);

}

//an anonymous function (with no name!)

//(We can't reference this without a name, so writing an anonymous function is

//not a valid statement)

function(person) {

console.log("Hello, "+person);

}

//anonymous function (value) assigned to variable

//equivalent to the version in the previous example

let sayHello = function(person) {

console.log("Hello, "+person);

}- You can think of this structure as equivalent to declaring and assigning an array

let myVar = [1,2,3]… just in this case instead of taking the anonymous array (right-hand side) and giving it a name, we’re taking an anonymous function and giving it a name!

Thus you can define named functions in one of to ways: either by making an explicitly named function or by assigning an anonymous function to a variable:

//these produce the same function

function foo(bar) {}

let foo = function(bar) {}The only difference between these two constructions is one of ordering. When the JavaScript interpreter is initially reading and parsing the script file, it will put variable and function declarations into memory before it executes any of the file. In effect, JavaScript will seem to “move” variable and function declarations to the top of the file! This process is called hoisting (declarations are “hoisted” to the top of the script). Hoisting only works for named function declarations: assigning an anonymous function to a variable will not hoist that function’s definition:

In practice, you should always declare and define functions before you use them (put them all at the top of the file!), which will reduce the impact of hoisting and allow you to use either construction.

11.2 Object Functions

Moreover, functions are values, so they can be assigned as values of object properties (since object properties are like name-spaced variables):

//an object representing a dog

let dog = {

name: 'Sparky'

breed: 'mutt'

}

//assign an anonymous function to the `bark` property

dog.bark = function(){

console.log('woof!');

}

//call the function

dog.bark(); //logs "woof!"- Again, this is just like how you can assign an array as an object’s property. With an array value you would use bracket notation to use it’s “special power”; with a function value you use parentheses!

This is how we can create an equivalent of “member functions” (or methods) for individual objects: the dog object now has a function bark()!

- Similar to Java, you can refer to the object on which a function is called using the keyword

this. Note that the manner in which thethisvariable is assigned can lead to some subtle errors when using callback functions (below). For more details, see the chapter on ES6 features. As a brief example:

// An object representing a Dog

let fido = {

name: "Fido",

bark: function() { console.log(this.name, "woofs")}

}

// An object representing another Dog

let spot = {

name: "Spot",

bark: function() { console.log(this.name, "yips")}

}

console.log('***This is Fido barking:***');

fido.bark(); //=> "Fido woofs". Note, `this` will refer to the `fido` object.

console.log('***This is Spot barking***');

spot.bark(); //=> "Spot yips". Note, `this` will refer to the `spot` object.11.3 Callback Functions

Finally, functions are values, so they can be passed as parameters to other functions!

//create a function `sayHello`

function sayHello(name){

console.log("Hello, "+name);

}

//a function that takes ANOTHER FUNCTION as an argument

//this function will call the argument function, passing it "world"

function doWithWorld(funcToCall){

//call the given function with an argument of "world"

funcToCall("world");

}

doWithWorld(sayHello); //logs "Hello world";In this case, the doWithWorld function will execute whatever function it is given, passing in a value of "world".

Important note: when we pass

sayHelloas an argument, we don’t put any parentheses after it! Putting the parentheses after the function name executes the function, causing it to perform the lines of code it defines. This will cause the expression containing the function to resolve to its returned value, rather than being the function value itself. It’s like passing in the baked cake rather than the recipe page.function greet() { //version with no args for clarity return "Hello"; } //log out the function value itself console.log(greet); //logs e.g., [Function: greet], the function console.log(greet()); //logs "Hello", which is what `sayHello()` resolves to

A function that is passed into another is commonly referred to as a callback function: it is an argument that the other function will “call back to” and execute when needed.

function doLater(callback) {

console.log("I'm waiting a bit...");

console.log("Okay, time to work!");

callback(); //"call back" and execute that function

}

function doHomework() {

// ...

};

doLater(doHomework);Functions can take more than one callback function as arguments, which can be a useful way of composing behaviors.

function doTogether(firstCallback, secondCallback){

firstCallback(); //execute the first function

secondCallback(); //execute the second function

console.log('at the same time!');

}

function patHead() {

console.log('pat your head');

}

function rubBelly() {

console.log('rub your belly');

}

//pass in the callbacks to do them together

doTogether(patHead, rubBelly);This idea of passing functions are arguments to other functions is at the heart of functional programming, and is what gives it expressive power: we can define program behavior primarily in terms of the behaviors that are run, and less in terms of the data variables used. Moreover, callback functions are vital for supporting interactivity: many built-in JavaScript functions take in a callback function that specifies what should occur at some specific time (e.g., when the user clicks a button).

Often a callback function will be defined just to be passed into a single other function. This makes naming the callback somewhat redundant, and so it is more common to utilize anonymous callback functions:

//name anonymous function by assigning to variable

let sayHello = function(name){

console.log("Hello, "+name);

}

function doWithWorld(funcToCall){

funcToCall("world");

}

//pass the named function by name

doWithWorld(sayHello);

//pass in anonymous version of the function

doWithWorld(function(name){

console.log("Hello, "+name);

});In a way, we’ve just “copy-and-pasted” the anonymous value (which happens to be a function) into the

doWithWorld()call—just as you would do with any other anonymous variable type.Look carefully at the location of the closing brace

}and parenthesis)on the last line. The brace ends the definition of the anonymous function value (the first and only parameter todoWithWorld), and the parenthesis ends the parameter list of thedoWithWorldfunction. You need to include both for the syntax to be valid!- And since anonymous functions can be defined within other anonymous functions, it is not unusual to have lots of

})lines in your code.

- And since anonymous functions can be defined within other anonymous functions, it is not unusual to have lots of

Closures

Functions are values, so not only can then be passed as parameters to other functions, they can also be returned as results of other functions!

//This function produces ANOTHER FUNCTION

//which greets a person with a given greeting

function makeGreeterFunc(greeting){

//explicitly store the param as a local variable (for clarity)

let localGreeting = greeting;

//A new function that uses the `greeting` param

//this is just a value!

let aGreeterFunc = function(name){

console.log(localGreeting+" "+name);

}

return aGreeterFunc; //return the value (which happens to be a function)

}

//Use the "maker" to create two new functions

let sayHello = makeGreeterFunc('Hello'); //says 'Hello' to a name

let sayHowdy = makeGreeterFunc('Howdy'); //says 'Howdy' to a name

//call the functions that were made

sayHello('world'); //"Hello world"

sayHello('Dave'); //"Hello Dave"

sayHowdy('world'); //"Howdy wold"

sayHowdy('partner'); //"Howdy partner"In this example, we’ve defined a function

makeGreeterFuncthat takes in some information (a greeting) as a parameter. It uses that information to create a new functionaGreeterFunc—this function will have different behavior depending on the parameter (e.g., it can say “Hello” or “Howdy” or any other greeting given). We then return this newaGreeterFuncso that it can be used later (outside of the “maker” function).When we then call the

makeGreeterFunc(), the result (a function) is assigned to a variable (e.g.,sayHello). And because that result is a function, we can call it with a parameter! ThusmakeGreeterFuncacts a bit like a “factory” for making other functions, which can then be used where needed.

The most significant part of this example is the scoping of the greeting variable (and its localGreeting alias). Normally, you would think about localGreeting as being scoped to makeGreeterFunc—once the maker function is finished, then the localGreeting variable should be lost. However, the greeting variable was in scope when the aGreeterFunc was created, and thus remains in scope (available) for that aGreeteFunc even after the maker function has returned!

This structure in which a function “remembers” its context (the in-scope variables around it) is called a closure. Even though the localGreeting variable was scoped outside of the aGreeterFunc, it has been enclosed by that function so it continues to be available later. Closures are one of the most powerful yet confusing techniques in JavaScript, and are a highly effective way of saving data in variables (instead of relying on global variables or other poor programming styles). They will also be useful when dealing with some problems introduced by Asynchronous Programming

11.4 Functional Looping

Another way that functional programming and callback functions specifically are utilized is to replace loops with function calls. For a number of common looping patterns, this can make the code more expressive—more clearly indicative of what it is doing and thus easier to understand. Functional looping was introduced in ES5.

To understand functional looping, first consider the common for loop used to iterate through an array of objects:

let array = [{...}, {...}, {...}];

for(let i=0; i<array.length; i++){

let currentItem = array[i]; //convenience variable for current item

//do something with current item

console.log(currentItem);

}While this loop may be familiar and fast, it does require extra work to manage the loop control variable (the i), which can get especially confusing when dealing with nested loops (and nested data structures are very common in JavaScript!)

As an alternative, you can consider using the Array type’s forEach() method:

let array = [{...}, {...}, {...}];

//function for what to do with each item

function printItem(currentItem){

console.log(currentItem;)

}

//print out each item

array.forEach(printItem);The forEach() method goes through each item in the array and executes the given callback function, passing that item as a parameter to the callback. In effect, it lets you specify “what to do with each element” in the array as a separate function, and then “apply” that function to each elements.

forEach()is a built-in method for Arrays—similar topush()orindexOf(). For reference, the “implementation” of theforEach()function looks something like:Array.forEach = function(callback) { //define the Array's forEach method for(let i=0; i<this.length; i++) { callback(this[i], i, this); } }In effect, the method does the job of managing the loop and the loop control variable for you, allowing you to just focus on what you want to do for each item.

The callback function give to the

forEach()will be executed with up to three argument (in order): (1) the current item in the array, (2) the index of the item in the array, and (3) the array itself. This means that your callback can contain up to three arguments, but since all arguments are optional in JavaScript, it can also be used with fewer—you don’t need to include an argument for the index or array if you aren’t utilizing them!

While it is possible to make a named callback function for forEach(), it is much more common to use an anonymous callback function:

//print each item in the array

array.forEach(function(item){

console.log(item);

})This code can almost be read as: “take the

arrayandforEachthing execute thefunctionon thatitem”.This is similar in usage to the enhanced for loop in Java.

Map

JavaScript provides a number of other functional loop methods. For example, consider the following “regular” loop:

function square(n) { //a function that squares a number

return n*n;

}

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

let squares = []; //the transformed array

for(let i=0; i<numbers.length; i++){

let transformed = square(numbers[i]); //call our square() function

squares.push(transformed); //add transformed to the list

}

console.log(squares); // [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]This loop represents a mapping operation: it takes an original array (e.g., of numbers 1 to 5) and produces a new array with each of the original elements transformed in a certain way (e.g., squared). This is a common operation to apply: maybe you want to “transform” an array so that all the values are rounded or lowercase, or you want to map an array of words to an array of their lengths, or you want to map an array of values to an array of <li> HTML strings. It is possible to make all these changes using the above code pattern: create a new empty array, then loop through the original array and push the transformed values onto that new array.

However, JavaScript also provides a built-in array method called map() that directly performs this kind of mapping operation on an array without needing to use a loop:

function square(n) { //a function that squares a number

return n*n;

}

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

//map the numbers using the `square` transforming function

let squares = numbers.map(square);

console.log(squares); // [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]The array’s map() function produces a new array with each of the elements transformed. The map() function takes as an argument a callback function that will do the transformation. The callback function should take as an argument the element to transform, and return a value (the transformed element).

- Callback functions for

map()will be passed the same three arguments as the callback functions forforEach(): the element, the index, and the array.

And again, the map() callback function (e.g., square() in the above example) is more commonly written as an anonymous callback function:

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

let squares = numbers.map(function(item){

return item*item;

});Note: the major difference between the .forEach method and the .map method is that the .map method will return each element. If you need to create a new array, you should use .map. If you simply need to do something for each element in an array, use .forEach.

Filter

A second common operation is to filter a list of elements, removing elements that we don’t want (or more accurately: only keeping elements that we DO want). For example, consider the following loop:

function isEven(n) { //a function that determines if a number is even

let remainder = n % 2; //get remainder when dividing by 2 (modulo operator)

return remainder == 0; //true if no remainder, false otherwise

}

let numbers = [2,7,1,8,3]; //an initial array

let evens = []; //the filtered array

for(let i=0; i<numbers.length; i++){

if(isEven(numbers[i])){

evens.push(numbers[i]);

}

}

console.log(evens); //[2, 8]With this filtering loop, we are keeping the values for which the isEven() function returns true (the function determines “what to let in” not “what to keep out”; a whitelist), which we do by appending the “good” values to a new array.

Similar to map(), JavaScript arrays include a built-in method called filter() that will directly perform this filtering:

function isEven(n) { //a function that determines if a number is even

return (n % 2) == 0; //true if no remainder, false otherwise

}

let numbers = [2,7,1,8,3]; //an initial array

let evens = numbers.filter(isEven); //the filtered array

console.log(evens); //[2, 8]The array’s filter() function produces a new array that contains only the elements that do match a specific criteria. The filter() function takes as an argument a callback function that will make this decision. The callback function takes in the same arguments as forEach() and map(), and should return true if the given element should be included in the filtered array (or false if it should not).

And again, we usually use anonymous callback functions for

filter():let numbers = [2,7,1,8,3]; //an initial array let evens = numbers.filter(function(n) { return (n%2)==0; }); //one-liner!(Since JavaScript ignores whitespace, we can compact simple callbacks onto a single line. ES6 and Beyond describes an even more compact syntax for such functions).

Because map() and filter() are both called on and produce arrays, it is possible chain them together, calling subsequent methods on each returned value:

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

//get the squares of EVEN numbers only

let filtered = numbers.filter(isEven);

let squares = filtered.map(square);

console.log(squares); //[4, 16, 36]

//or in one statement, using results anonymously

let squares = numbers.filter(isEven)

.map(square);

console.log(squares); //[4, 16, 36]

This structure can potentially make it easier to understand the code’s intent than using a set of nested loops or conditionals: we are taking numbers and then filtering for the evens and mapping to squares!

Reduce

The third important operation in functional programming (besides mapping and filtering) is reducing an array. Reducing an array means to aggregate that array’s values together, transforming the array elements into a single value. For example, summing an array is a reducing operation (and in fact, the most common one!): it reduces an array of numbers to a single summed value.

- You can think of

reduce()as a generalization of thesum()function found in many other languages—but rather than just adding (+) the values together,reduce()allows you to specify what operation to perform when aggregating (e.g., multiplication).

To understand how a reduce operation works, consider the following basic loop:

function add(x, y) { //a function that adds two numbers

return x+y;

}

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

let runningTotal = 0; //an accumulated aggregate

for(let i=0; i<numbers.length; i++){

runningTotal = add(runningTotal, numbers[i]);

}

console.log(runningTotal); //15This loop reduces the array into an “accumulated” sum of all the numbers in the list. Inside the loop, the add() function is called and passed the “current total” and the “new value” to be combined into the aggregate (in that order). The resulting total is then reassigned as the “current total” for the next iteration.

The built-in array method reduce() does exactly this work: it takes as an argument a callback function used to combine the current running total with the new value, and returns the aggregated total. Whereas the map() and filter() callback functions each usually took 1 argument (with 2 others optional), the reduce() callback function requires 2 arguments (with 2 others optional): the first will be the “running total” (called the accumulator), and the second will be the “new value” to mix into the aggregate. (While this ordering doesn’t influence the summation example, it is relevant for other operations):

function add(x, y) { //a function that adds two numbers

return x+y;

}

let numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]; //an initial array

let sum = numbers.reduce(add);

console.log(sum); //15The reduce() function (not the callback, but reduce() itself) has a second optional argument after the callback function representing the initial starting value of the reduction. For example, if we wanted our summation function to start with 10 instead of 0, we’d use:

//sum starting from 10

let sum = numbers.reduce(add, 10);Note that the syntax can be a little hard to parse if you use an anonymous callback function:

//sum starting from 10

numbers.reduce(function(x, y){

return x+y;

}, 10); //the starting value comes AFTER the callback!The accumulator value can be any type you want! For example, you can have the starting value be an empty object {} instead of a number, and have the accumulator use the current value to “update” that object (which is “accumulating” information).

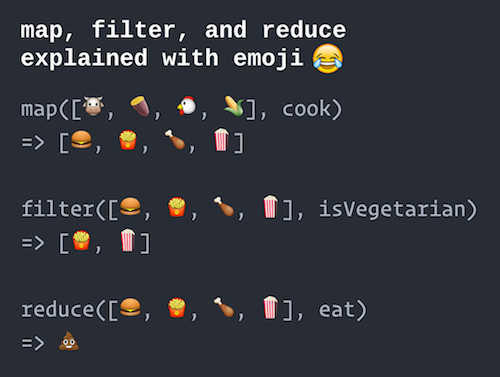

To summarize, the map(), filter(), and reduce() operations work as follows:

Map, filter, reduce explained with emoji. Not valid JavaScript syntax.

All together, the map, filter, and reduce operations form the basic platform for a functional consideration of a program. Indeed, these kinds of operations are very common when discussing data manipulations: for example, the famous MapReduce model involves “mapping” each element through a complex function (on a different computer no less!), and then “reducing” the results into a single answer.

11.5 Pure Functions

This section was adapted from a tutorial by Dave Stearns.

The concept of first-class functions (functions are values) is central to any functional programming language. However, there is more to the functional programming paradigm than just callback functions. In a fully functional programming language, you construct programs by combining small, reusable, pure functions that take in some inputted data, transform it, and then return that data for future use. Pure functions have the following qualities:

- They operate only on their inputs, and make no reference to other data (e.g., variables at a higher scope such as globals)

- They never modify their inputs—instead, they always return new data or a reference to an unmodified input

- They have no side effects outside of their outputs (e.g., they never modify variables at a higher scope)

- Because of these previous rules, they always return the same outputs for the same inputs

A functional program sends its initial input state through a series of these pure functions, much like a plumbing system sends water through a series of pipes, filters, valves, splitters, heaters, coolers, and pumps. The output of the “final” function in this chain becomes the program’s output.

Pure functions are almost always easier to test and reason about. Since they have no side-effects, you can simply test all possible classes of inputs and verify that you get the correct outputs. If all of your pure functions are well-tested, you can then combine them together to create highly-predictable and reliable programs. Functional programs can also be easier to read and reason about because they end up looking highly declarative: it reads as a series of data transformations (e.g., take the data, then filter it, then transform it, then sort it, then print it), with the output of each function becoming the input to the next.

Although some functional programming zealots would argue that all programs should be written in a functional style, it’s better to think of functional programming as another tool in your toolbox that is appropriate for some jobs, and not so much for others. Object-oriented programming is often the better choice for long-running, highly-interactive client programs, while functional is a better choice for short-lived programs or systems that handle discrete transactions (like many web applications). It’s also possible to combine the two styles: for example, React components can be either object-oriented or functional, and you often use some functional techniques within object-oriented components.

- Indeed, the latest versions of Java—a highly object-oriented language—add support for functional programming!

If you are interested in doing more serious functional programming in JavaScript, there are a large number of additional libraries that can help support that:

There are also many languages that were designed to be functional from the get-go, but can be compiled down into JavaScript to run on web browsers. These include Clojure (via ClojureScript) and Elm.

Resources

- Functional Programming in JavaScript a fantastic interactive tutorial for learning functional programming in JS

- Higher Order Functions a chapter from the online textbook Eloquent JavaScript

- Scope & Closures an online textbook with an extremely detailed explanation of scoping in JavaScript